Kriste aghdga (Christ is Risen) is an important Easter hymn in the Georgian Orthodox tradition. Many musical variants of the paschal troparion exist, as detailed on our main page, which includes a pronunciation guide, videos, notation, and performance practice tips!

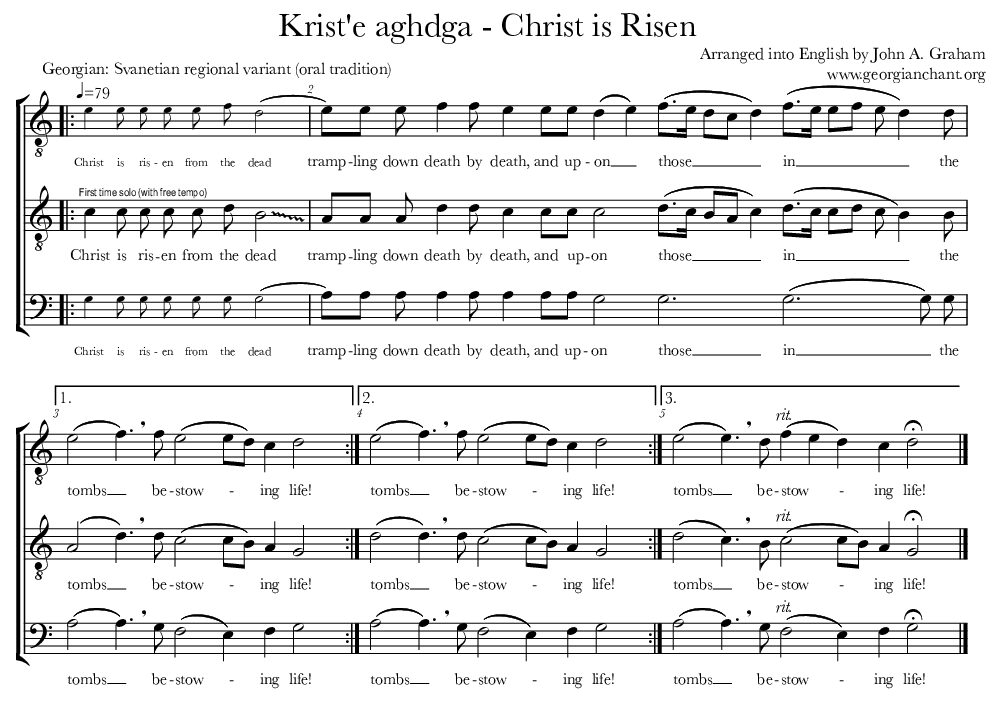

But sometimes, a choir is looking to sing Orthodox music set in the English language. On this page, we present arrangements of the Georgian paschal troparion in English, with discussion on the editing process.

Enjoy, and please leave your comments!

Arrangement Process

The first challenge for an arranger is to find a suitable compromise between the translated text and the original music without losing the integrity of either.

An arranger needs to think about the following:

- Identify syllable count differences in the text;

- Identify places where the music can be changed-modified-adapted to the new text;

- Attempt to set important words to important climactic musical moments;

- Identify musical moments that should be retained as integral to the piece, vs. moments where music can be changed to serve the text-setting requirements.

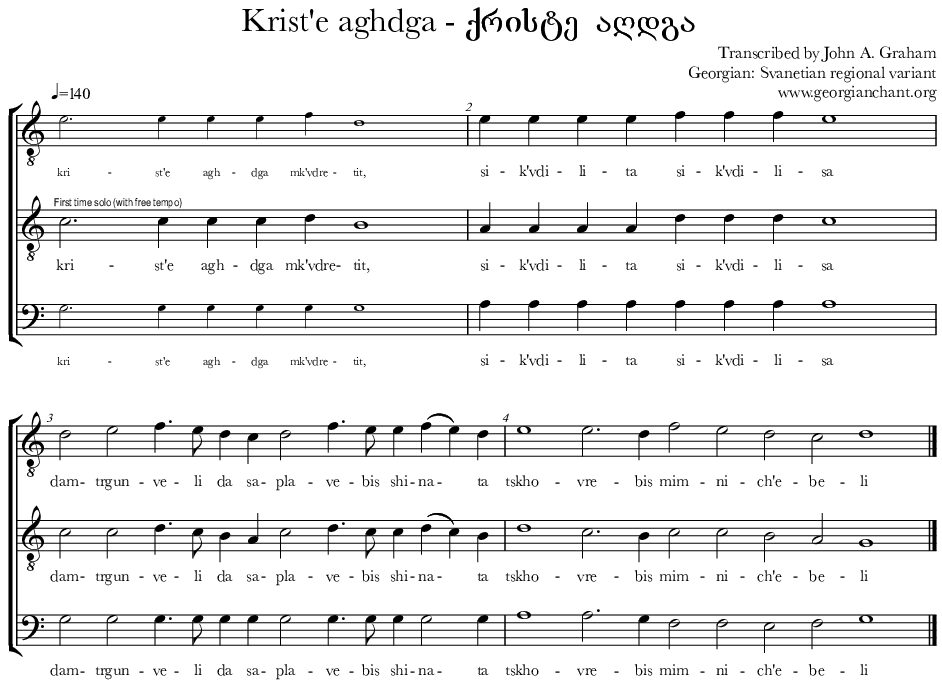

- Balance important musical moments vs. important text;

In this chant, the Georgian text has 34 syllables while the English text only has 24 syllables. The four-syllable word sikvdilita in Georgian translates as the one-syllable word death, while the word saplavebis translates as tombs. This is actually a good problem to have, as having more syllables of text than the original would present additional challenges.

Georgian: kriste aghdga mkvdretit, sikvdilita sikvdilisa, damtrgunveli da saplavebis shinata tskhovrebis mimnichebeli!

English: Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs restoring life!

The Georgian chant emphasizes the word tskhovrebis (life) with a long held musical note at the beginning of measure 4. Unfortunately, in the English translation, the word life is at the very end of the text, so there is no avoiding its setting as the final note of the piece. The arranger must choose at this point which English word to place in the climactic musical moment in measure 4.

The choices are few. It can either be tombs or be-stow-ing. As one can see, I chose tombs, which forces the words those in the into a highly melismatic arrangement to cover the ten notes preceding, in measure 3. The text bestowing life can then be spread evenly over the final cadential bar, which to my sensibilities feels more appropriate than the other available options.

So the challenge for the arranger is two-fold:

With less syllables, where are we going to spread out the English text, and with different moments of emphasis in the two texts, how are we going to set the English text appropriately, without dramatically changing the source music?

With the end of the text-setting completed, the rest of the text setting easily falls into place. Here are a couple of points to consider:

Textual Rhythm:

In the second musical phrase, the text sikvdilita sikvdilisa is sung to a basic recitative, the music of which can be modified to fit the cadence of the English text, trampling down death by death. As an unaccented language, Georgian texts sung in recitative typically receive the same duration for each syllable. Thus this text in the Georgian original score receives only quarter notes for each syllable. But as an accented language, I find that it is appropriate to emphasize accented syllables in English using rhythm. Thus, the two instances of the word death receive quarter-note length treatment, while smaller words are set to quicker eighth notes in a manner that more approximates the rhythm of spoken English.

Opening Declamation:

The opening text on the "chanting note" is the all-important declamation "Christ is Risen!" In Georgia, this text is sung by a soloist signifying the entrance to the tomb at the beginning of the all-night Paschal vigil. Because this opening phrase defines the musical setting, it seems important to keep it as similar to the original as possible. In the middle ages, with longer or shorter texts, chanters simply added or reduced the number of syllables sung to the opening "chanting note." But in this case, we want to keep the opening declamation intact, thus requiring us to set the remaining text across the subsequent musical phrases.

Text-setting decisions:

In measure 2 of the Georgian text, we have the four-syllable words sikvdilita sikvdilisa (death by death), which musically feels like a recitative whose music could be reduced or expanded. The English text trampling down precedes death by death, for a total of six syllables which, even though the words are out of order, almost matches the eight syllables in the Georgian phrase. The musical climax in measure 3 is given to the important verb damtrgunveli (trampling) in the Georgian, but the English word trampling has already occurred in measure 2. It is somewhat underwhelming to set this musically climactic moment to the relatively insignificant English words, and upon, which must follow if we are to observe proper word order.

The closest word of significance would be those. So we place those on the climactic musical chord in measure 3, which helps us arrange measure 2. What is the best way to set the text and upon into the fabric of the preceding music without damaging any musical conventions of Georgian chant? I've chosen to add and up- to the recitative notes in measure 2, while -on leads us through tension building chords at the beginning of measure 3 to the musical climax.

When teaching kriste aghdga to international singers, I try to impress upon them the importance of singing this particular variant in a performance practice that is appropriate the region of its origin (Svaneti), which is also what lowland Georgian singers emulate when they sing this highland variant. Characteristics of Svanetian performance practice can be observed in the many recordings of folk music that abound on the internet today, or in live performances in Georgia.

For example, they sing open-throated, loudly and boldly, with ringing overtones especially in the close-harmony dissonant chords which characterize Svanetian harmony (chords including 5-4-1 interval distribution, such as D-C-G, as on the word tombs in most variants). They don't mind a few glissandos. The traditional tuning tends sharp, as the extremely bright sound pushes the outer limits of the open-fifth chords between the outer voices, while the middle voice tends to sing closer than a whole tone to the top voice when singing the 5-4-1 chords. Thus through repetition, the entire chant intentionally drifts sharp.

Voice Distribution:

The chant begins, by unusual convention among Georgian liturgical chants, with a soloist singing the opening declamation. On subsequent repeats, the entire choir sings the first phrase "Christ is Risen from the dead" (see small note heads in the outer voice parts, measure 1).

The upper voice parts are most often sung by soloists, while the rest of the singers support with the lowest voice part. As the text is repeated many times throughout the Paschal service, different singers often take turns singing the upper voice parts. If there is a large choir, a director may choose to ask more singers to join the upper voice parts, but the lowest voice should always have more singers than the upper voice parts to provide the correct balance.

Most Georgian choirs would choose to sing this chant with either a section of men (tenor-tenor-bass), or women (soprano-soprano-alto). This way the natural timbre shines through. In no cases should the octave be doubled by low basses. The performance pitch of the chant should be chosen based on the personnel, it can be sung at any register high or low.

The first, second, and third endings present only some of the possible ornamental cadential variations that might be encountered among Georgian traditional singers.

We welcome your questions and comments!

Dave Froman

Lots of tough decisions but I think you’ve made all the right ones, including time signature and where to split the measures.